July 18, 2022 BY W. T. Whitney

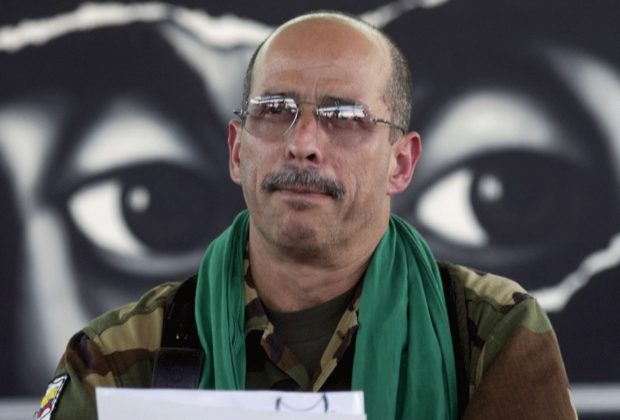

.Simón Trinidad’s 72nd birthday is July 30. Don’t think about sending him a card. U.S. prison authorities have blocked his mail since 2004. He is lodged in a maximum-security federal prison in Colorado. Extradited from Colombia, he remained in solitary confinement until 2018.

As a leader of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), Trinidad was in charge of political education and propaganda. He was captured in Ecuador in 2003, with CIA assistance. He had been conferring there with a United Nations official about the release of FARC-held prisoners.

Transferred to Colombia, Trinidad was a high-profile prisoner. He had family connections with upper elements of Colombian society and had been a lead FARC negotiator in peace talks with Colombia’s government from 1998 to 2002. The Colombian government and its U.S. ally might have detected a propaganda advantage in a public trial and severe punishment. Putting him away, out of sight, as a prisoner of war in Colombia would have offered little gain.

Ideas may also have cropped up that Trinidad extradited would be an object lesson for Colombia’s political dissidents, display damage done to the FARC, and advertise the newly strengthened U.S.-Colombian alliance. Colombian officials asked the U.S. government to request his extradition.

The U.S.’ “Plan Colombia” took effect in the early 2000s. At the cost eventually of more than $10 billion, the U.S government provided military equipment, intelligence services, and funding for Colombia’s military, police, and prisons. The purpose, claims the U.S. Global Leadership Coalition was “to provide security and economic development assistance to help combat the spread of narcotics…and promote economic growth.”

Narco-trafficking was actually a secondary matter. Plan Colombia was mainly about fighting leftist insurgents, primarily the FARC. A stiffened alliance was the background to the targeting of Trinidad and to enhanced political oppression in Colombia.

Interviewed recently, Colombian historian Renán Vega Cantor mentions “80 years, during which Colombia became the main U.S. ally in the region.” He cites seven U.S. military bases, “a U.S. presence in 50 [other] places …[and] 25 secret U.S. agencies” operating in Colombia. Crucially, the paramilitaries, long notorious as agents of deadly violence, are “Colombian Army proxies sponsored, financed, trained, and supported by the United States, which have carried out all kinds of atrocities that the Armed Forces, openly, cannot legally carry out.”

Says Vega Cantor, “Plan Colombia militarized [Colombian] society in an impressive way, propelling the growth of the Colombian Armed Forces to unthinkable levels.” Colombia presently fields 500,000 troops; its army is one of the world’s largest. Some 50,000 Colombian military and police officers received training at the U.S. Army’s School of the Americas in Georgia, referred to by some as the “school of assassins.”

The U.S. government has readily accepted the cruelty marking its partner’s civil war. Cruelty was on display recently. The Truth Commission, set up via the 2016 Peace agreement between the FARC and the Colombian government released its ten-volume Final Report on June 28, 2022. Cruelty portrayed there is vast enough to have infected the criminal justice system of its ally, or so it seems.

Analyst Camilo Rengifo Marín, referring to the Report, takes note of “an armed conflict of more than 60 years that goes on still and led to more than 10 million victims of whom 80% were civilians.” He writes that “50,770 were kidnapped, 121,768 disappeared, 450,664 murdered, and 7.7 million forcibly disappeared.” Another observer indicates that, “The report is critical of the role played by various U.S. administrations in developing security policies, in militarizing society, and in hiding relations between paramilitary groups and the Colombian Army.”

The Final Report itself states that, “During many years, the victims got little attention and often were defended only by human rights organizations or by churches. From torture victims and kidnappings by guerrillas…to victims belonging to political movements like the Patriot Union and other opposition groups, those victims were invisible to most Colombians over the course of decades.”

Simón Trinidad has been all but invisible in the United States. U.S. authorities sought his extradition solely because of alleged narco-trafficking. After all, international law does forbid extradition on political grounds, like rebellion. The indictment greeting Trinidad on arrival in Washington charged him with providing material support to terrorists, taking hostages, and dealing in illicit drugs.

It took four trials between 2006 and 2008 to exonerate him on the charges of narco-trafficking and providing material support for terrorists and to convict him of conspiring to capture three U.S. drug-war contractors. FARC gunfire had brought down their plane. The idea of conspiracy derived exclusively from Trinidad’s status as a FARC member.

In 2008, 57-year-old Trinidad received a 60-year sentence. Since 2018, he’s been allowed to eat a midday meal in a dining hall. Phone calls are rare. Emails and periodicals are prohibited, along with letters. Trinidad’s only visitors are his lawyers and rarely his brother and Colombians conferring about Peace-Agreement arrangements.

Trinidad faces charges in Colombia relating to possible crimes committed during the Civil War. The Peace Agreement provided for a “Special Jurisdiction for Peace” (JEP in Spanish) whose role is to decide on punishment or pardon for former combatants on both sides charged with crimes. To be pardoned they must tell the truth.

Trinidad is eligible to appear before the JEP. His U.S. lawyer Mark Burton indicated via email that a first step towards his virtual appearance there is for Colombia’s Foreign Ministry to ask the U.S. Justice Department to approve of Trinidad’s appearance before the JEP.

Burton is hopeful. The new foreign minister of the incoming Gustavo Petro government may be receptive; Álvaro Leyva Duran “worked on the negotiating team of the FARC in Havana” during the peace talks, Burton recalls. The JEP could pardon Trinidad or require court appearances in Colombia. Either way, pressure would mount for the U.S. government to commute his sentence to allow for deportation.

President-elect Gustavo Petro, campaigning, protested the ongoing killings of community leaders and former FARC combatants. A central demand of his Historical Pact coalition has been the full implementation of the 2016 peace agreement. Ultimately, relief for Trinidad rests on realizing peace in Colombia.

Any affinity of the U.S. government with the goals of the new Historical Pact government would be good news for Trinidad. For the United States to back away, even a little, from intervening in Colombia would also be good news. Secretary of State Blinken, speaking with Petro, “underscored our countries’ shared democratic values and pledged to further strengthen the 200-year U.S.-Colombia friendship,” according to an announcement on June 20. The mouthing of hypocrisy is bad news.

Peace in Colombia, and Trinidad’s fate, depends on the U.S. relaxing its cop-on-the-beat posture for an entire region, that of monitoring any and all stirrings of fundamental political and social change. A new kind of U.S. openness, however, doesn’t jibe with the U.S. determination to protect the interests of corporations and the moneyed classes at home and abroad.

Until a new anti-imperialist consciousness has inspired a meaningful and potentially effective, all-point opposition, collective effort is in order now towards organizing and fighting for Simón Trinidad’s return to Colombia. Even so, that struggle would have to fit within a larger context of anti-imperialism, peace now in Colombia, and support for the new government there.