APRIL 7, 2015

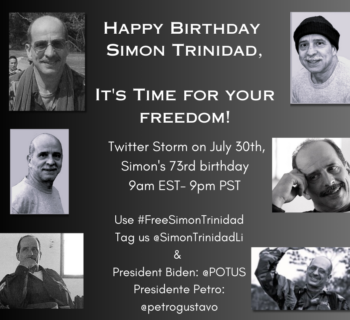

Simon Trinidad, Imprisoned, Connects with Colombian Peace Process

Ricardo Palmera, alias “Simon Trinidad,” is a political prisoner and more. Even as such, his sixty-year sentence and constant solitary confinement are extraordinary. Post- sentencing legal services are not always available. His mail is blocked, visitors are limited, and he is shackled when they see him. Trinidad occupies a “Supermax” cell in the United States, in Colorado. In Colombia he’s an enemy of the state.

Simon Trinidad was a leader of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) with responsibilities for political education, financial overview, and peace negotiations. He participated with the FARC in talks with the Colombian government in 1998-2002. In Ecuador prior to his capture in January 2004 – with CIA help – he was preparing to meet with United Nations representative James Lemoyne to review the situation of FARC prisoners of war.

On being detained, Trinidad was moved to Colombia, and then on December 31, 2004 he was extradited to the United States. Colombia had asked U.S. authorities to request his extradition. The United States at the time had no outstanding charges against him and Colombian officials had to fashion allegations. Later Colombian courts convicted Trinidad in absentia, and he faces jail time there.

Trinidad, although imprisoned in the United States, remains a political force beyond prison walls. The FARC’s negotiations with the Colombian government to end civil war there began in Cuba in November 2012. The FARC still regards Trinidad as one of its leaders, and at the outset of the talks, the guerrillas named Trinidad as one of their five accredited representatives to the negotiations. In group photos he stands with other FARC negotiators as a life-sized “cut-out” image.

The FARC has repeatedly demanded his release from prison so he can serve as a negotiator. Rumors circulated recently that Colombian officials, listening to the FARC, are asking U.S. counterparts for Trinidad’s release.

Negotiators now dealing with the post-conflict fate of guerrilla leaders are discussing issues having to do with imprisonment and extradition. Critics say Colombia’s tendency to extradite prisoners to the United State States is problematic for Colombian sovereignty. Simon Trinidad is a case in point.

Trinidad personifies another point of contention. Are FARC soldiers criminals or are they soldiers fighting in a war? Terms bandied about such as “banditry,” “terrorism,” and “drug-running” suggest the former. But to the extent that the FARC’s anti-government rebellion led to internal armed conflict, FARC guerrillas are fighting a civil war.

The latter view squares with international law, which recognizes the right of revolution. If a peace settlement accepts that notion, then prisoners are exchanged and they return home. Meanwhile, it’s illegal under international law for civil war combatants like Trinidad to be sent off to a foreign land.

U.S. accusers said Trinidad helped the FARC kidnap three U.S. contractors after their reconnaissance airplane had been shot down by FARC guerrillas in 2003. The U. S. claim is that the hostages were civilians who were fighting drug traffickers. But their FARC captors saw them as military contractors deployed under Plan Colombia, the mechanism through which the U.S. military took on leftist guerrillas in Colombia. The contractors went free in 2008.

At his first trial, in late 2006, Simon Trinidad faced five charges. Three of them each carried the accusation of conspiring to kidnap one of the three captive contractors. Two more charges had implications for the so-called U.S. war on terrorism. Prosecutors charged Trinidad with membership in a hostage-taking conspiracy, also with providing “material support to terrorists,” namely the FARC. Conviction on either charge would have suited the larger U.S purpose of imprisoning adversaries anywhere who could be portrayed as “terrorists.” It was the time then when prisoners of war were morphing into “unlawful combatants.” In 1997 the U.S. State Department identified the FARC as a terrorist organization.

But Simon Trinidad told jurors about his life story and why the FARC was fighting. His presentation, even in translation, was convincing enough for jurors to refuse to convict him on any charge.

Then the Justice Department had to find a new judge for the second trial. The first judge had illegally talked with jurors to gain information about their deliberations that would assist prosecutors in the second trial. That trial ended with Trinidad being convicted on the single charge of conspiracy to take the contractors hostage. He was sentenced in early 2008. Two subsequent trials on allegations of narco-trafficking ended in mistrials.

Trinidad was a member of Colombia’s elite. When on December 5, 1987 Ricardo Palmera – he was not yet Simon Trinidad – left his home city of Valledupar, in Cesar department, to join the Caribbean Bloc of the FARC, he left behind a family, his bank- managing job, an economics professorship at a local university, and family assets which he managed – a cattle ranch and cotton and fruit- growing properties.

His father had been a respected lawyer, law professor, and Colombian senator for the Liberal Party. His maternal grandfather had served as governor of Santander. The future prisoner attended a private secondary school in Bogota with a “strong social and democratic ethos.” He studied at a naval academy in Cartagena, where President Juan Manuel Santos was a fellow student. Trinidad graduated in economics from a private university in Bogota and obtained a master’s degree in business economics from Harvard University in the United States.

In Valledupar, Palmera/ Trinidad joined the “New Liberalism” party, which after 1982, locally at least, became “Common Cause.” That organization would later affiliate with the Patriotic Union (UP by its Spanish initials) which emerged following a peace agreement between the government and the FARC. Demobilized guerrillas, Communists, and other leftists entered electoral politics as U.P candidates. They achieved victories, and then fell victim to nationwide slaughter. In Valledupar in 1987, many of Trinidad’s Common Cause comrades died, one by one. Others went into exile. One of them, in her published recollections, described the climate of fear and desperation. Trinidad stayed.

The Colombian Army cracked down on Common Cause members in 1982. With others, Palmera was arrested, “handcuffed, taken … to Barranquilla in a cattle truck, deprived of sleep, food, and water for three days, subjected to cruel interrogation, and released after five days.” At his first trial Trinidad identified the murder of charismatic UP presidential candidate Jaime Pardo Leal on October 11, 1987 as a watershed moment. He’d had a meeting with Pardo Leal scheduled for the next day.

All of this is Trinidad’s story. His case is complicated, and for the sake of further elucidation, an interview conducted on March 21, 2015 with Denver lawyer Mark Burton appears below. Burton has recently undertaken to serve as Simon Trinidad’s lawyer in the United States. El Espectador reporter Maria Flores interviewed him in Bogota. Burton discusses Trinidad’s possible release from prison in relation to the peace negotiations.

* * *

El Espectador: Is it actually possible the U.S. government might free “Simon Trinidad?”

Mark Burton: I think it’s really feasible, because the decision to put him at liberty is in the hands of President Barack Obama. Colombia needs Trinidad at the peace talks; he is a well-informed man, capable, and brings his experience of having been a negotiator at the Caguán [peace talks] during the government of Andrés Pastrana. The FARC has accredited him as one of its representatives and it’s crucial that he be in Havana.

EE: Is there a favorable atmosphere within the Obama administration for dealing with an eventual release?

MB: I can’t speak for the U. S. government, but I can certainly tell you in this regard that for Obama to have designated Bernard Aronson as a delegate to the peace process is very important. It’s a clear sign that the President of the United States supports the talks and to that extent I think there are great possibilities. Legally, just as Obama has the power to pardon somebody, he can also reduce a sentence. That would be the most effective way, although everything depends on overtures the Santos government makes.

EE: Have they looked at possible opposition from civil society in the United States?

MB: Look, last December, when the United Stated freed the three Cuban agents, there was a lot of noise, because the Cuban exile community in Florida is very strong. But Colombia is very different. In that sense, I don’t think the scenario would be particularly unfavorable.

EE: What possibilities might “Trinidad” expect in U.S. courts?

MB: He was sentenced to 60 years in prison thanks to pressure at the time from the Colombian government. Later he lost his appeal. But we are reviewing the case and looking at alternatives. I want to make it clear that it’s been very difficult for him to pursue his defense, because at key times there was no lawyer available for him to rely on. The public defender he had during the trial has maintained contact with him strictly on a basis of friendship and human rights. Beyond that, he’s been kept in absolute isolation now for 11 years. That violates the [United Nations] Convention against Torture.

EE: Do you share the theory that his trial in the United States had a political tinge?

MB: I think it was a set-up, of course. [Colombian President]Alvaro Uribe requested that the U.S. government ask for Simon Trinidad’s extradition. Because the United States told him that no charges were pending against him, the Colombian government looked for supposedly trustworthy information to use for extraditing him. He was never convicted because of drug-trafficking, never because of terrorism, but instead through what happened to some CIA contractors. He never knew them, and furthermore, they were deployed in a war zone. Uribe wanted to punish Simon Trinidad, and there are many reasons making one think this was a political trial.

EE: Aren’t you exaggerating to suggest that U. S. justice lent itself to fashioning a “set-up” for a guerrilla chief?

MB: George Bush and Alvaro Uribe were good friends. One couldn’t say they talked about all this over a cup of coffee, but there was an understanding between the two governments. Besides, no one can be extradited for political reasons.

EE: In Colombia people wondering about a possible settlement make the point that victims deserve justice. How do you respond?

MB: In this country there are many kinds of victims. It’s been brought up in the negotiations, for example, that political prisoners also have to be recognized as victims. The peace process is justifiably looking toward an end to armed conflict and to the possibility of social peace so that no one will be victimized any longer. Political considerations do exist that some want settled in the courts. Even though there are sectors in Colombia who want to continue the war, we believe Colombians support the process and that, in the end, Uribe and his friends will be in the minority. If you weigh the choice for a country like Colombia between having peace and having a prisoner in the United States, anyone can definitely see that peace is more important.

The Spanish-language version of the interview is accessible at: http://www.elespectador.com/noticias/judicial/hay-grandes-posibilidades-de-simon-trinidad-sea-liberad-articulo-550490 W. T. Whitney Jr. translated.